Translated from the Korean by Anastasia Traynin

In August 2021, shortly after finishing graduate school, I happened to come across a call for translations for K-Book Translation Contest, a new contest put on by the 한국출판문화산업진흥원 (Publication Industry Promotion Agency of Korea). They had selected five books in five different categories (Literature, Humanities, Philosophy, Social Sciences, Youth). Contestants were instructed to choose one of the books and translate the first chapter (or introduction, in some cases) into one of four languages: English, Chinese, Spanish, Vietnamese. Since my specialty is social issues, naturally I chose the Social Sciences category, for which the selected book was 오준호 (Oh Jun-ho)’s 평등, 헤아리는 마음의 이름 (translated by me as Equality, the Name for a Considerate Mind). My translation of the introductory chapter of this book tied for second place with another translation of the same work, with the results announced in November, just after author Oh Jun-ho had begun his 2022 presidential campaign as a candidate of the 기본소득당 (Basic Income Party). In addition, the fight to pass an anti-discrimination law promoting equality for all Korean residents continues with no resolution and an ongoing campaign in 2022.

As of now, the translations have not been published on other platform and we have not received feedback beyond our prizes. Below is my translation in its submitted form. Any suggestions, corrections, general comments or inquiries are welcome.

********

Equality, the Name for a Considerate Mind

Part 1: Asking the Meaning of Equality in the Age of the Misery Olympics

Story One.

“We are all equal. Therefore, no one should be given special treatment.”

This is the experience of a physically disabled university student who used a wheelchair. When registering for classes, this disabled student carefully checked whether or not the lecture hall had stairs, in order to avoid one that would be difficult to access with a wheelchair. Since the course registration guide had indicated a lecture hall without stairs, the student registered and went to class on the first day only to find a lecture hall with stairs. The course registration guide had been wrong. With the help of friends, the disabled student was able to enter the lecture hall, but as a result missed the first 20 minutes of class.

The student asked the administration office if the classroom could be changed to one without stairs, but was told that classroom assignments were completed and could not be changed. Feeling sorry, the professor proposed to the student, “After every class, I’ll give you a separate session to make up the first 20 minutes.” Non-disabled students who heard this came forward in protest. Claiming unfairness, they demanded to know why the make-up class was only for the disabled student. With everyone competing for good grades, why was the disabled student getting special treatment? In viral social media posts, some of the class members even labeled the disabled student a “nuisance.” In the end, the disabled student dropped the class.

Hearing this story brought to mind a saying by the 19th century writer Anatole France: “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.” To sleep under a bridge means to be homeless, such as the homeless people at Seoul Station. A law forbidding the rich as well as the poor to be homeless may seem equal, but is that really the case? Would a rich person ever sleep under a bridge in the first place?

Samsung Electronics Vice Chairman Lee Jae-yong homeless at Seoul Station is as unimaginable as a rich person sleeping under a bridge. Those who sleep there are poor people unable to find livable housing, left with no choice but to lay down under a bridge. The law gives priority to measures of urban aesthetics that effectively only punish the poor and drive them out of the city. Of course, streets from where the poor have disappeared look more comfortable and safe for the rich. In this way, when the law’s standard is biased towards one side, it may appear fair and impartial from the outside while actually oppressing one side and protecting the privilege of the other. Anatole France satirizes the fact that the law claims to be fair but is actually serving the interests of the rich.

pg. 10 Photo Caption: [A homeless person under a bridge with a paper cup that poses a question]

The non-disabled students’ position does not seem to come from an arrogant belief that the non-disabled are superior to the disabled. Rather, their attitude presupposes that “We are all equal.” It comes from the idea that since everyone has to get good grades to squeeze through the narrow door of employment, all are in the same boat and standing at the same starting line in the grades race. So the non-disabled students get angry and claim unfairness, demanding to know why anyone should get special consideration under mutually equal circumstances. But they are missing one thing: though they may be unaware, the fact is that they have “privilege.”

The non-disabled students may think, “But how could I, a regular person, possibly have any privilege?” Their lack of a disability is a daily privilege, one that allows them to come and go from a lecture hall with stairs without any difficulty. For a disabled student, just coming and going from a lecture hall with stairs takes a big physical and mental toll. Under the premise of all being equal, the non-disabled students say that disabled students shouldn’t be given any “special treatment.” Yet without even realizing it, they enjoy non-disabled privilege; they are the ones angry over the fact that they won’t share this privilege with disabled students.

Equality is an important value, but there are countless different answers to the question “What makes something equal?” Treating the same things as the same and things that are not the same differently is what we call “fairness.” In that case, asking “What makes something equal?” must also be asking what makes it fair. If we provide equal opportunities and apply the rules equally, does this make the world fair enough? Or is there something else needed? This is the theme discussed in this book.

Story Two.

“Inequality is a problem. However, there should be a bigger difference in rewards based on ability.”

While giving a lecture to a group of teenagers, I asked, “Do you think inequality and polarization are serious problems in Korea?” Among the 20 teenagers listening to the lecture, around 17 or 18 answered “yes.” I followed up with the question, “Do you think there should be bigger rewards based on ability and effort?” This time, out of the 20 people, 100% answered “yes.” The teenagers mostly empathized with the so-called “golden spoon, dirt spoon” reality of inequality as a serious problem. On the other hand, they almost unanimously agreed with the idea that bigger rewards should be based on ability and effort.

This response was rather interesting, as the teenagers’ two answers seemed to contradict one another. The idea that there should be a big difference in rewards based on ability and effort is called “meritocracy.” If one supports meritocracy, then it makes sense to consider income inequality as an inevitable result, since performance will also differ according to each person’s different abilities. When I asked the same questions at another lecture for teenagers, the same somewhat contradictory responses emerged. However, when you think about it, even while supporting meritocracy, today’s inequality may still not be seen as the fair result of ability and effort.

Today’s teenagers have had a sense of inequality since childhood. In one family, when a child has a birthday, the parents invite their child’s friends to a birthday party at a high-class buffet. In another family, both parents work long hours and can hardly even provide a good meal, so the children make do with ramen at an internet cafe. In one family, the child has a famous academy lecturer come to their house for expensive private tutoring and goes abroad for language study during school holidays. In another family, the child goes to a local supplementary academy and has to earn their spending money working a part-time job during the holidays. The gap between these experiences is borne out by the numbers. The top 10% of society hold 50% of the total national income and account for 70% of the real estate and 80% of the interest and stock dividends.

On the other hand, among 18 million working people, 9 million earn an average of less than 2 million won per month. Among the self-employed, 70%, or 3.5 million people also barely earn 2 million won per month. This means that half of Korea’s economically active population gets by on less than 2 million won per month.

Yet even while experiencing inequality, meritocracy dictates that this kind of unequal reality can only be overcome by the individual. If you improve your ability and make far more of an effort, you can expect to be able to climb at least a little higher up the ladder in this stratified society. Society tells some of us, “You lagging behind is due to your lack of effort and ability,” while claiming that people who occupy high places got there thanks to their own ability and effort and are therefore qualified for their current wealth and status. Is this a true statement? Can each person really overcome this reality through their own ability and effort? Did people of wealth and status come to occupy their place through ability and effort alone?

Story Three.

“Competition is absolutely necessary. Even if competition makes me miserable.”

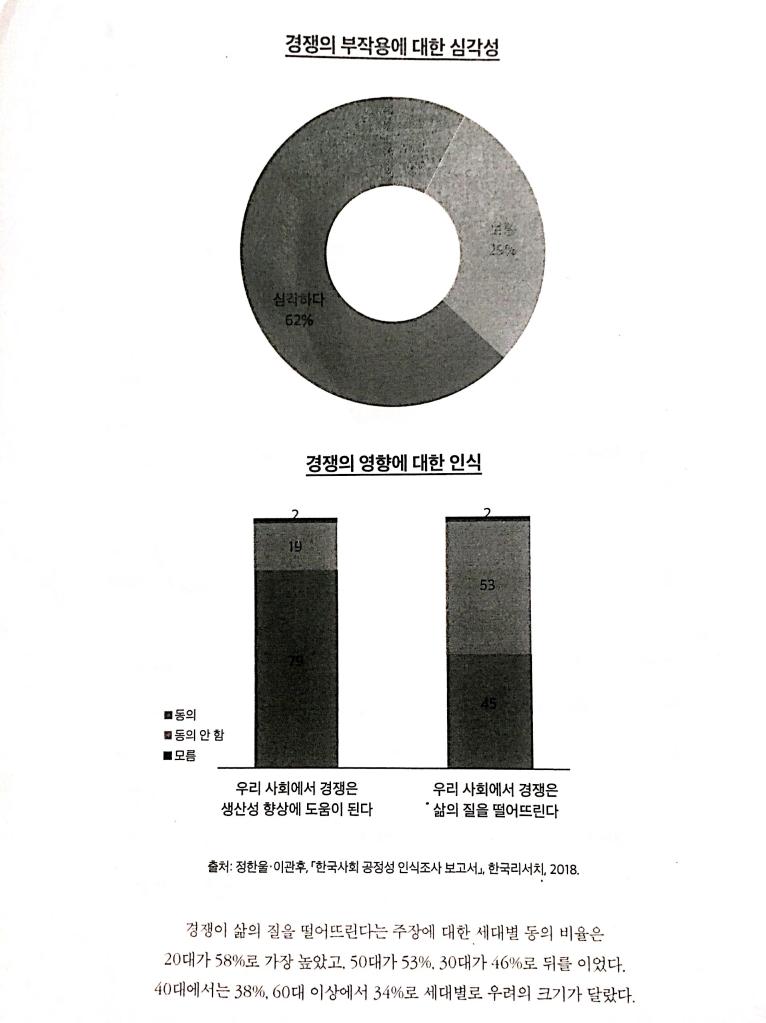

Looking at the public opinion poll on the right, 79% of respondents answered that competition helps to increase productivity. Yet 62% of respondents in the same poll think that the side effects of competition are serious. Only 8% answered that they are not serious. People accept the value of competition, while at the same time have a hard time because of it. Among all respondents, the total number that agreed with the statement “Competition lowers quality of life” was 45%, just under half. However, among respondents in their 20s, 58% agreed with this statement. It makes sense that the younger the generation, the more they feel competition fatigue. When I ask teenagers this question, a similarly contradictory response emerges. “Competition makes life difficult. Still, we can’t get rid of competition, right?”

Are the Side Effects of Competition Serious?

I Don’t Know – 1%

Not Serious – 8%

Normal – 29%

Serious – 62%

Awareness of Competition’s Influence

Competition Helps to Increase Productivity in our Society

I Don’t Know – 2%

Disagree – 19%

Agree – 79%

Competition Lowers Quality of Life in our Society

I Don’t Know – 2%

Disagree – 53%

Agree – 45%

Source: Jeong Han-wool, Lee Gwan-ho, “Report: Survey on Awareness of Fairness in Korean Society,” Hankook Research, 2018.

The percentage of people in agreement with the statement “Competition lowers quality of life in our society” was the highest for people in their 20s at 58%, followed by people in their 50s at 53% and people in their 30s at 46%. For people in their 40s and people in their 60s and above, agreement stood at 38% and 34%, respectively.

In a society where everyone is competing for dear life, it’s hard to see better results than anyone else. Even with quite a lot of achievements, there is nowhere to stand out. To be ahead of the competition, one needs to show results, but if the results are indistinguishable from one another, how can one person stand out? You must claim to be competing in a more unfavorable circumstance than others. You must say that you carried a bigger load and that your running track was far bumpier than the rest. In this way, even if your results are the same as others, it could be said that you have more ability and that you made more of an effort. Comparing hardship becomes a new competition event. It’s called the “Misery Olympics.”

The Misery Olympics are all the rage in our society. If someone admits, “These days, this or that is giving me a hard time,” no one comforts or encourages them. Instead, they diminish the other person’s suffering and point out how much worse they themselves have it, saying, “That’s nothing. You should see what I’m going through…” Rather than a medium of empathy with others, suffering has become a means of competition and something to put on display. The participants in the Misery Olympics are steadily increasing. Even though this battle takes place among friends or groups with similar circumstances, it is also happening between men and women, as well as between different generations.

When someone complains, “I failed the test,” the other person responds, “I couldn’t even apply.” When an irregular worker talks about experiencing discrimination, the other person throws back, “Do you know how hard it is to prepare for a job interview?” When women talk about their experience with sexism, men refute with, “Do you know how much we struggle during military service?” When the younger generation talks about “Hell Joseon,” the older generation comes back with, “Do you know about the harsh dictatorship times?” At the Olympic Games, the happy winner and the loser congratulating the winner, joined together with the audience applauding in praise and encouragement makes for a touching scene. But at the end of the Misery Olympics, there is no happy winner, no loser who gains strength from the thought “I’m less unfortunate than that one,” and the people looking on don’t feel any better. It’s just everyone, together, becoming more miserable than before.

Everyone has a chance to participate in competition and the grand prize is called “equal opportunity.” This is the alpha and the omega of what people know about equality. However, in this society, people are becoming more worn out and unhappy. The winner of the competition seems to be competition itself. This is because the only thing gradually growing stronger is the unwavering faith that competition is necessary and important. Should equality be considered the same as “fair competition,” as though it only refers to equal opportunity? In the long history of humankind, has the reason to fight for equality come down to equally enjoying the freedom to compete until collapsing?

What is the word Confucius taught you to practice for the rest of your life?

The above three stories show the difficulties that our society faces. When turned on its head, the act of upholding fairness and criticizing “special treatment” can be viewed as seeking to protect one’s own vested interests. Social inequality and polarization are gradually increasing and everyone is full of discontent over no longer getting a fair reward based on their own ability and effort. However, pursuing “meritocracy” leads to a larger wealth gap over time. Furthermore, people believe that competition plays a positive role while at the same time making them more worn out and unhappy. The “Misery Olympics” reveals the paradox catching up with the age of 30,000 dollars GDP per capita.

While equality is an important value with deep historical roots, it needs to be reinterpreted based on time period and context. The reality we are facing is asking us to find a new path within the above-mentioned contradictory and conflicting situation surrounding equality. To this end, we must reexamine the value of equality and talk to each other. This book was written to outline some necessary questions for this kind of discussion.

- Why is equality an important value?

- Are inequality and polarization serious to the point where they can’t be left as they are?

- Is inequality based on ability and effort a justifiable gap?

- Is it fair to think that ability and effort should determine the size of the reward?

- What should free and equal citizens do to achieve fair distribution?

- Should we only pursue equal opportunity? Is an equal outcome totally impossible?

From the following chapter, we will look together for the answers to these kinds of questions. Before that, I will introduce a story that may help those of us exploring equality and fairness. It is from The Analects of Confucius: Wei Ling Gong.

Confucius’ student Zi Gong asked, “Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one’s life?” Confucius replied, “Is not reciprocity such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.”

In this text, the Chinese character “恕”(Shù) literally means “forgiveness.” Here, the meaning of forgiveness is “to fathom” by becoming the same in heart and mind. Confucius considered humans as beings who must live with others, and to do so it is necessary to be considerate of the situations of others. When taking or not taking a certain action towards another, ask yourself, “If I were that person, would I gladly accept the choice that I am about to make?” and only take action when the answer is, “This choice would be acceptable to anyone.” In the Aesop fable “The Fox and the Stork,” if the two animals knew how to fathom and be considerate of the other, the fox wouldn’t serve the stork a meal in a shallow dish and the stork wouldn’t serve the fox a meal in a tall jar.

In this case, “to fathom” goes beyond the level of etiquette that simply requires not making the other party feel bad. It is a question of establishing a principle of justice. This will be discussed later in the book, but the fact is that the standard for justice doesn’t just appear out of nowhere. Rather, it is a rule agreed upon through a fair process, by equal citizens deciding to equally respect each others’ interests. In particular, the focus of the debate on justice is how to share valuable things among members of society and when it is necessary to allow a difference in distribution. This kind of justice is called “distributive justice.”

When thinking about distributive justice, or rather fair distribution, the necessary attitude is the above-mentioned forgiveness that means to fathom and consider the other. This attitude means breaking free from only being interested in whether or not my personal interests decreased or the idea that if something is an important value or standard for me, others must also accept it without question. It means thoroughly considering each other’s situations, putting ourselves in others’ shoes, carefully examining the context and situation, and making a judgment without bias towards any particular interest.

In the spirit of fathoming, let’s navigate the way towards just relationships between equal citizens.

For more information on the K-Book Translation Contest, visit the website (Korean): https://k-booktranscon.kr

For an English-language description of the Basic Income Party in Korea, view and download this PDF: https://basicincome.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Oh-Basic-Income-party-manifesto.pdf

The Anti-Discrimination Law (Equality Act) coalition website (mostly Korean) can be found here: https://equalityact.kr